Pintor, astrónomo y naturalista, matemático, sociólogo y estadístico:

Translate

Dramatis Personae

- Daniel Scarfò

- Filopolímata y explorador de vidas más poéticas, ha sido traductor, escritor, editor, director de museos, músico, cantante, tenista y bailarín de tango danzando cosmopolita entre las ciencias y las humanidades. Doctor en Filosofía (Spanish and Portuguese, Yale University) y Licenciado y Profesor en Sociología (Universidad de Buenos Aires). Estudió asimismo Literatura Comparada en la Universidad de Puerto Rico y Estudios Portugueses en la Universidad de Lisboa. Vivió también en Brasil y enseñó en universidades de Argentina, Canadá y E.E.U.U.

Categorías

lunes, 30 de diciembre de 2024

domingo, 29 de diciembre de 2024

Victor Papanek

Diseñador, educador, antropólogo. Aquí un enlace a su fundación, un video didáctico sobre su figura y una charla que diera en Apple:

jueves, 26 de diciembre de 2024

Charles Kay Ogden

Linguista, filósofo, escritor, editor, psicólogo, traductor, que se aventuro asimismo en la política, las artes y la filosofía:

miércoles, 25 de diciembre de 2024

Andrés Laguna

(Retrato de Andrés Laguna publicado en su traducción anotada de Dioscórides, por Mathias Gast, 1570.)

Médico humanista, farmacólogo, botánico, filósofo, políglota, viajero, poeta y político:

martes, 24 de diciembre de 2024

lunes, 23 de diciembre de 2024

Y llegaron las "fiestas"

domingo, 22 de diciembre de 2024

Gustav Fechner

Filósofo, psicólogo, profesor de física, publicó artículos sobre química y también se afanó en demostrar que otros seres vivos distintos a nosotros, empezando por las plantas, tienen consciencia:

sábado, 21 de diciembre de 2024

Deserción

Allí está, quieto, adormecido, haciendo el tambo como todas las madrugadas.

Allí está, cargando el tarro como puede y dejando al gato lamer la leche derramada.

Ata al ternero luego, para que aprenda de chico a tomar las sobras de lo que el patrón manda.

Mira el campo, se acerca a la bomba, se lava, se alisa el pelo con las manitas ajadas y, antes de ponerse el guardapolvo, se las calienta en el brasero recién encendido por la mama.

No toma nada, no tiene tiempo, quiere salvarse del reto diario por la llegada tarde.

Mientras corre entre los almácigos seguido por los perros, escucha las campanadas.

Se para...piensa que no lo van a comprender...y se vuelve a las casas.

Margot, 1984

(Escrito por mi madre cuando era directora de la Escuela 144 en el Barrio La Foresta, Km. 36,800, González Catán)

viernes, 20 de diciembre de 2024

Adiós, Beatriz Sarlo

lunes, 16 de diciembre de 2024

Charles and Ray Eames

Diseñadores industriales con impacto en la arquitectura y el mobiliario y trabajo en diseño gráfico, bellas artes y cine:

Ver también:

Y el Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity

domingo, 15 de diciembre de 2024

António Damasio

Antonio Damasio, neurocientífico. Profesor de Psicología, Filosofía y Neurología. Aquí en una reciente entrevista: Antonio Damásio, neurocientífico: “Hacer un trasplante de cabeza sería como juntar a dos criaturas”

sábado, 14 de diciembre de 2024

John Cage

Compositor, escritor, poeta, profesor universitario, musicólogo, filósofo, pintor, teórico de la música, ilustrador, dibujante, micólogo y artista visual:

Decivilization May Already Be Under Way

Decivilization May Already Be Under Way (complete text)

"We already understand many of the conditions that make a society vulnerable to violence. And we know that those conditions are present today, just as they were in the Gilded Age: highly visible wealth disparity, declining trust in democratic institutions, a heightened sense of victimhood, intense partisan estrangement based on identity, rapid demographic change, flourishing conspiracy theories, violent and dehumanizing rhetoric against the “other,” a sharply divided electorate, and a belief among those who flirt with violence that they can get away with it. These conditions run counter to spurts of civilizing, in which people’s worldviews generally become more neutral, more empirical, and less fearful or emotional."

¿Qué es educar?

Escrito por mi madre hace 40 años (1984)

viernes, 13 de diciembre de 2024

Charles Babbage

Matemático, informático teórico, inventor, economista, filósofo, profesor universitario, ingeniero, astrónomo y escritor:

jueves, 12 de diciembre de 2024

Al-Razi

Médico y filósofo que realizó aportes además a química y la física, escribiendo además sobre lógica, astrología y gramática:

miércoles, 11 de diciembre de 2024

Benjamín Bratton

Sociólogo cuyo trabajo abarca la filosofía, la arquitectura, el diseño, las ciencias de la computación y la geopolítica:

Y aquí su charla Ted-anti-Ted:

martes, 10 de diciembre de 2024

lunes, 9 de diciembre de 2024

Peter S. Pallas

Zoólogo, botánico, etnógrafo, explorador, geógrafo, geólogo, naturalista, taxonomista. Fue el primero en describir este gato que hoy lleva su nombre:

domingo, 8 de diciembre de 2024

sábado, 7 de diciembre de 2024

jueves, 5 de diciembre de 2024

Francesco Algarotti

Filósofo, poeta, ensayista, crítico de arte, experto en newtonianismo, arquitectura y ópera. Sobre su figura y el networking en la Europa del siglo XVIII, ver esta tesis doctoral:

miércoles, 4 de diciembre de 2024

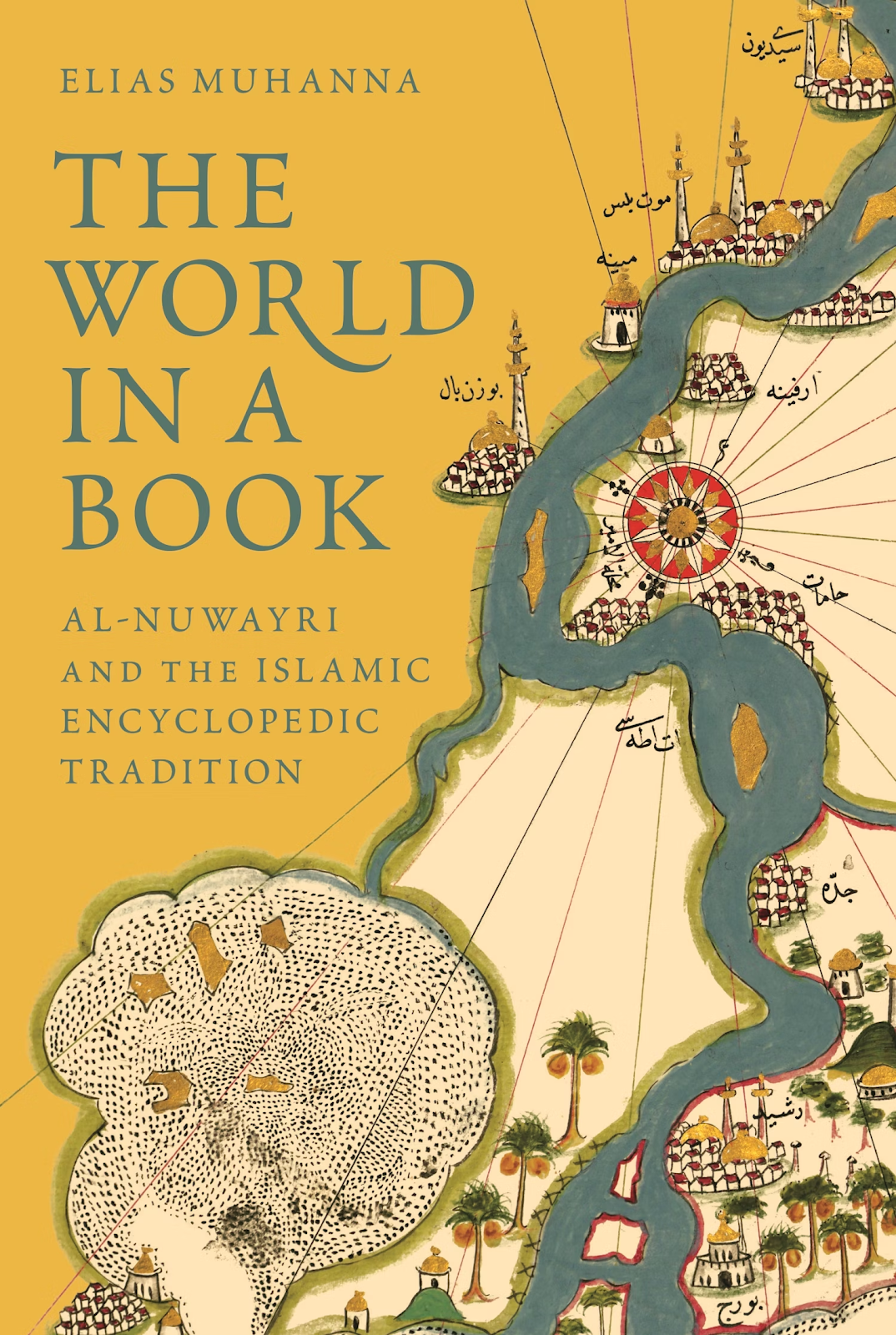

Al-Nuwayri

Polímata egipcio del siglo XIV, autor de una de las mayores enciclopedias del mundo islámico. Aquí la introducción a un libro sobre esa obra:

lunes, 2 de diciembre de 2024

Alfonso X El Sabio

Ese sobrenombre lo obtuvo por su actividad literaria, linguística, legislativa, histórica y astronómica:

domingo, 1 de diciembre de 2024

Identity in the making (published originally in Spanish in 2015 as "La identidad en fragua")

Identity in the making

Literature,

immigration and society in the Belle Époque (1880-1920)

We

sociologists know that when one type of society begins to emerge, the

other is not yet dead. That is exactly what happened in Argentina in

the years corresponding to the so-called Belle Époque, whose

end around 1920 already showed a population predominantly of

immigrant origins of one or two generations and, along with it, an

aristocratic world in decomposition. For the same reason, foreigners

who had enjoyed the possibility of high social mobility in the times

prior to 1870 would lose it later when it was restricted to families

of other Latin American or European elites1.

Meanwhile,

in literature, the works marked the relative success that rogues and

upstarts could achieve at that time in their purposes, which can be

seen in En la sangre (1887) by Eugenio Cambaceres,

Irresponsable (1889) by Manuel Podestá and La bolsa (1891)

by Julián Martel. Cambaceres' novels represent the first

manifestations of naturalism in the River Plate region. They take

sides with the well-off classes and disapprove immigration in the

last quarter of the 19th century since it did not fit, supposedly,

with the country project dreamed of by those sectors.

Juan

Agustín García and José María Ramos Mejía highlighted the

absence in Buenos Aires of an aristocracy with lineage like those of

Lima or Chuquisaca.2

According to Losada, the genealogy and composition of high society,

added to social mobility and the consolidation of a capitalist logic

that made wealth the main pillar of the social position, made it

increasingly difficult to speak of an aristocracy in Buenos Aires.

The structural transformation that was taking place in society

allowed Daireaux to foresee that:

…little by

little, a very different aristocracy will be reconstituted from the

old one in which it will not be enough to be a descendant from a

patrician of old Creole lineage, from a leading figure of the

Independence or of more modern times, or even from a well-known

person; only the possession of a real estate fortune would allow

access to it”3

A

renewal crossed the political, economic and intellectual elites of

1880 and 1920 as a consequence of the transformation of society and

the recomposition of the population due to immigration, which was one

of the privileged goals of the modernization program of the second

half of the 19th century. But, with the first strikes at the

beginning of the 20th century, the initial enthusiasm and optimism

regarding the role of the immigrant began to decline until the latter

even occupied the position of the unwanted, the guilty of all the

“evils” that began to afflict the Argentine lands. The “evils”

of modernization were converted into “evils” of immigration. From

there it was believed that through regulations such as the Law of

Residence, for example, and persecutions of the “foreign element”

that controlled its presence in the country, the “evils” would

disappear.

| When the bill authorizing the expulsion from the

country of any foreigner believed to be “compromising national

security or causing disturbances in public order” was discussed in

Congress, few congressmen, including Carlos Pellegrini (son of

immigrants), protested the implications that such a measure would

have: discouragement of immigration, abandonment of the liberal

tradition.

In

January 1919, after a violent return of the immigration wave, the

great metalworkers strike took place, in which almost all of its

participants were immigrants and which would culminate in the famous

“tragic week.” These events constitute an example of what was

brewing in the social imagination: liberal cosmopolitanism was

beginning to generate a phenomenon of the opposite sign, conservative

nationalism. Every time one appears in Argentine history, the other

reappears. And the nationalists even propose themselves as an

alternative model of modernization, arguing that the Creole, the “son

of the homeland,” has far superior working and cultural conditions

than the immigrant. And that the latter would probably “set back”

the rural areas.

Horacio Quiroga’s story “El Hombre

Artificial” (1910) introduces us to two immigrants: the Russian

Donissoff, who arrives in Buenos Aires in 1905, and the Italian Marco

Sivel, who arrived a year earlier. Together with an Argentine born in

the capital, Ricardo Ortiz, they set up a laboratory with machines

and instruments brought from the United States. The experiment to be

carried out can be read as the construction of the nation. A Russian,

an Italian, a Creole, and the American instruments. The Argentine,

Ortiz, is pessimistic about it: “It can’t be done, Donissoff,

it’s impossible!” he points out. And we can say that there are

two “creatures.” One is Biogenic: the artificial man, and the

other is Ortiz himself. The experimenters seek to implant pain to

Biogenic. It is what he needs to be human, to be a country: to have

the experience, to have lived. To live, you need to have lived. But

there are two who have not lived, because Ortiz has not suffered yet.

So he has to earn that suffering by torturing. Ortiz hesitates and

finally kills Donissoff, which allows him to cry, to suffer. But, at

the same time, his suffering was the end of all utopian illusion:

“Everything was concluded.”

This pessimism regarding the

results of immigration can be extended to a good part of Latin

America and even to the United States where, in 1917, Congress passed

a law - over the presidential veto - prohibiting the admission of

foreigners who would not pass a reading and writing test: another of

the privileged figures of modernization along with the problem of

simulations that Ingenieros would study and that would later make

Haffner, Roberto Arlt's character, say: “I am civilized. I cannot

believe in courage. I believe in betrayal.”4

From

1880 onwards, Buenos Aires clearly abandoned its profile as a

pedestrian and Creole city. In 1884, Lucio V. López published La

gran aldea, a book he wrote with two parallel, though not

simultaneous, cities in mind: the still colonial Buenos Aires of 1860

and that of 1880, in whose excessive growth origins, languages and

cultures were mixed. In 1899, Eduardo Wilde published Prometeo y

Cia, with prints and chronicles from which images of a changing

city emerge and that the author explores with skepticism. And in

particular, with regard to the mixture of languages, Ernesto Quesada

inserted his criticism into the central debates of the 1990s on the

identity of the language and, therefore, of the Argentine in the face

of the arrival of the immigrant masses.5

For Quesada, the language considered “national” was that one of

the educated people and of the writers (not the “jargons” or that

other one of the foreigners) and he reflected on how to make the

inherited Spanish language one of his own. But it happened that

during the 19th century Italian immigration to South America had

surpassed that destined for North America, and it would begin to

leave its mark on the language. At the same time, Italy was the

country that contributed, in numbers incomparable with those of other

Latin American countries, the greatest number of immigrants to

Argentina. One of these Italian immigrants is the father of Genaro,

the main character of the novel En la sangre (1886), by

Eugenio Cambaceres. This story, based on the notions of social

Darwinism prevalent at the end of the century, shows us the immigrant

as someone who occupies the position of the worst in society. The

immigrant is seen there effectively as the social waste from which

comes Genaro, the son of immigrants who hates the liberal elites and

who, according to David Viñas, will reappear later in Mustafá and

Giacomo, by Armando Discépolo.6

His first contempt is for the liberal institution “par

excellence”: What is school for? The university appears

guarded by an ignorant Galician and Genaro, born of a degraded and

vile Napolitan, faces the eternal laws of blood, transmitted from

father to son. But he “was not born in Calabria but in Buenos

Aires, he wanted to be a Creole, generous and selfless like the other

sons of the earth.” Thus, he tries to find solace in the

vituperation of the Creole and the Spaniard:

Who

had been his caste, his grandparents? Brutal gauchos, commoners

raised with their feet on the ground, bastards of Indians smelling

of colts and Galicians smelling of filth, adventurers, upstarts,

spendthrifts, without God or law, job or benefit, the kind that

Spain sent by the boatload, that it threw in droves into the sewer of

its colonies; His parents were peddlers… He was the son of two

miserable gringos, but his parents had been married, he was a

legitimate son, his mother had been honest, he was not a son of a

bitch at least.”7

And

hatred and contempt lead him to go into debt, to lose the fortune of

his wife, daughter of creoles, whom he ends up threatening with

death: “…I will kill you one of these days, if you are

careless!”8

In

Irresponsable (1889), a book by Manuel Podestá that we have

already mentioned, we find the opposite position: here the immigrants

are seen as life givers and the “bad guys” are the creoles. The

author was the professional son of an immigrant who constructed a

wandering Jew from the university as a hero. The immigrants are

painted here as “aimless beings”, “wandering the streets like

birds without a nest”, “pariahs” who arrive in a cosmopolitan

city that improvises everything, where everyone makes a fortune

without great effort. With the Jewish mark, the immigrants are here

the caravan in search of a promised land.

Meanwhile and in

parallel to these processes, among some privileged members of the

generation of the 80s, the figure of the dandy writer will stand out

with his characteristic style full of digressions which will find an

appropriate mold in the literary talks or causeries, as

Mansilla calls them. Among the “talkers”, Eduardo Wilde and

Miguel Cané also stand out. In all of them, their travel stories are

key literature: Una salida a los indios ranqueles (An

excursion to the Ranquel Indians) (1870) by Mansilla, Viajes y

observaciones (Travels and observations) (1892) by Wilde and En

viaje (1884) by Cané. Distinguished and refined conversation was

defined by moderation, an attitude expected in nineteenth-century

behavior considered appropriate.9

Conversation in salons was thus a school of the so-called civilized

behavior. Lucio Victorio Mansilla, a paradigmatic causeur of his

generation, is the author of the important Entre nos. Causeries

del jueves (1889-1890): his talks, edited by himself and which

arose within the framework of the activities of his sister Eduarda’s

salon in Buenos Aires. His stories abound in anecdotes from the

private lives of public figures he knew and frequented. He cultivates

the audience with his witty words and his poise, threading together

memories, anecdotes, opinions, constructing a singular figure with

the aura of the liberal elite. The colloquial formula that gives the

work its title refers to an audience of peers marked by illustrious

characters capable of capturing winks, innuendos and ironies and

understanding quotes in French. But other texts were those that

narrated the city and what happened in it: Buenos Aires desde

setenta años atrás (1881) by José Antonio Wilde, Memorias

de un viejo (1889) by Víctor Gálvez10

and Las beldades de mi tiempo (1891) by Santiago Calzadilla,

construct a nostalgic image of the village city that they witnessed

and remembered then from its recent modernity.

The

intellectual world of those years, in a general climate of confidence

in “progress,” privileged “facts” and the search for

objective laws of society, according to the theories of Comte and

Spencer. It oriented the study of that society and its

representations according to mass psychology and social positivism,

with a concern for homogenizing the population that had been

numerically increased by immigration. At the same time, and without

being disconnected from the above, a growing relevance was given to

the “moral” question linked to the “undesired effects” of the

modernization project of the generation of the 1980s. Moral concern

was not only linked to the immigration issue: electoral fraud was

evident as well as the search for rapid enrichment through financial

speculation by important sectors of the ruling political class. It

was in the works of Agustín Álvarez, Carlos O. Bunge and, above

all, José Ingenieros, that the most notable reflections on this

subject could be appreciated, having Agustín Álvarez been the

precursor of this moralistic orientation.11

In Nuestra América (1903), Carlos O. Bunge describes

laziness, sadness and arrogance, which he supposed derived from

indigenous, black and Spanish societies, as illnesses of Hispanic

American politics. In El hombre mediocre (1913), Ingenieros

distinguishes the “idealist”, rebellious and maladjusted, from

the “mediocre man”, deceitful and easily tamed, and in Hacia

una moral sin dogmas (1917) he will lead the former towards a

solidary ethics.

Ingenieros himself was one of those

foreigners who had arrived in Argentina. And in the last years of the

19th century and the first years of the 20th century, in the press,

in congress, in literary works but also in the street, the changes

that immigration caused were discussed. There was full awareness of

the importance of the cultural transformations that were taking

place. For some, like Miguel Cané, they were devastating for the

country, going so far as to say that thousands of “criminals” and

“madmen” were arriving in Argentina destined to fill our prisons

or to be a slow poison for our society. Stereotypical images of

criminal immigrants began to appear in many articles published in the

Archivos de Psiquiatría y Criminología, where sociologists

accompanied the writers in the vituperative

characterization.

Miguel Cané was a central figure in this

process. From the Senate and in his writings he advocated the

prohibition of entrance for undesirable immigrants and the expulsion

of those who were already in the country. He maintained that national

preservation should be above liberal immigration policies. Hence, he

introduced the Bill for the Expulsion of Foreigners in the Senate on

June 8, 1899. At the time, the bill collided with the strong mesh of

a half-century-old tradition that postponed its promulgation,

although for a few years.

Among the sociologists who began to

affirm that Argentines were superior to immigrants - that even in

certain nationalities they would inherit strong tendencies to crime -

was Juan Bialet Massé, who in his Informe sobre el estado de la

clase obrera en la Argentina (1902) defended Creole work over

foreign work after a trip promoted by the Argentine government

throughout the country.

But the position of immigrants was

not only that of waste and evil. The problem was that waste and evil

were already beginning to be the majority. So, in the vision of

nationalism, we were facing a process that seemed irreversible, in a

country full of immigrants loaded with viruses in their blood, a

poisoned, sick “social body” that made it dangerous to live in.

We had to flee at least from the cities, cores of modernization and

mass immigration: that would be the end of the liberal city.

The

position of the immigrant would then intersect with that of the

criminal and the pretender. José Ingenieros himself, one of the

first successful immigrants, would understand these pretenders.

Pretenders and delinquents who could, like the farmer of El

casamiento de Laucha or the grocer of Juan Moreira, not

pay the honest worker what was owed. In the case of El casamiento

de Laucha (1906), by Roberto Payró, we hear the main character

say: “I charged the farmer two days’ wages (…) who took a few

cents from me like a good gringo.” Here the immigrant is also an

outcast who “went around like a ball without a handle” (in the

case of the Galician grocer who had become creole), or he is the

smart guy who comes to “make it in America,” like the priest. And

Laucha throws away everything he earned with work, ruins the grocery

store, “but also, what a party!”

Roberto Payró, who had

defended immigration so much, comes in 1909, in his Chronicles,

to review that position, maintaining that as a result of the massive

arrival of foreigners now “everything is anarchic, indecisive,

nebulous, insecure.” In the magazine Caras y Caretas of June

12 of that same year, in an article entitled “Dangerous

Immigration,” immigrants are fused with anarchists, speaking of the

latter as “changeable and unprincipled” adventurers, who only

seek to “create problems wherever they can.”

In 1911,

Italian immigration was suspended for a period of fourteen months.

The fact is that Italy did not want to accept the Argentine order for

sanitary inspection of ships arriving from there. Generosity toward

immigrants lost its disinterest - if it ever had any. In the United

States, journalists, intellectuals and politicians also saw

immigration as the origin of urban social problems.

In short,

between 1880 and 1920 the country was changing at a dizzying pace.

Political power was beginning to pass from an elite to a middle class

that was being formed in part thanks to the integration of these

immigrants. In this context, the modernist poets appeared, led by

Rubén Darío. However, the most outstanding for Argentina was

Leopoldo Lugones, who gave the famous lectures in 1913 at the Odeón

theatre (collected in 1916 under the title El payador) in

which he canonised Martín Fierro “to provide the country with its

own epic like any civilized nation has”.

The fact that the

figure of the gaucho became a symbol of national tradition in the

early years of the 20th century - when until then it had been an

emblematic representation of resistance to authority and of Creole

barbarism - favoured the exaltation of the humble origins of

important sectors of high society: having "gaucho" origins

then ceased to be a sign of a rudimentary ancestry to reflect an

intimate connection with the roots of the nation.12

The nationalist sermons, both that of Lugones and that of Ricardo

Rojas, sought to oppose Europeanism and to install the features of

its own tradition in the construction of Argentine cultural and

literary history

A few years earlier (1905), on the other

side of the cultural tradition, the Podestá brothers had brought

Marco Severi to the stage of the Rivadavia Theater, a drama by

Payró in which he opposed the xenophobic ideas of the men of his

generation. In it he attacked the law of extradition and residence of

foreigners in the country. Marco Severi is the story of an

immigrant who has committed a crime in his homeland but who leads an

honest life in Argentina. And a year earlier, when Gregorio de

Laferrère staged ¡Jettatore! and Roberto J. Payró did the

same with Sobre las ruinas, Florencio Sánchez premiered La

gringa, which will postulate the final harmonious synthesis

between the gringo and the criollo who confront each

other in the countryside: their children get married. The mixture of

languages, the Argentine speech far from the castizo norm, and the

local conflicts caused by economic misery and political corruption

are favorite ingredients of theater companies and the public.

Florencio Sánchez understands this and continues to satisfy this

demand in his works.

The sainete criollo genre will be

a product of this with its costumbrismo and the conventillo as

a meeting place, a crossing of foreigners and compadres, where

caricatured habits and slang are condensed, not without humor. In the

festive farce Tu cuna fue un conventillo (1920), by Alberto

Vacarezza, for example, the public laughs “with” the characters

who manage to overcome social or romantic problems in the courtyard

of the tenement, a true “melting pot of races.”13

We

see then how immigrants as bilingual communities draw borders and

provoke a debate about inclusions/exclusions in society. From the

great optimism of 1853, we were moving on to pessimism at the

beginning of the century and the crises of 1919 and 1929/30.14

The immigrant who had occupied the place of the ideal in Facundo in

1845, the figure of the “summoned” in the Constitution of 1853,

the spoiled child of the generation of the 80s, little by little

became the “ugly and disturbing upstart” of Las multitudes

argentinas by José María Ramos Mejía, the “hidden danger”

of the1902 Residence Law, and the violent and execrable anarchist of

1919.

There is another central character in these years that

we have not yet included in this story. This is Eduardo L. Holmberg,

the prototype of the man of the generation of the 80s who not only

took charge of spreading Darwinism, positivism and the advances of

science in the country, but he was also a precursor of the fantastic,

police and science fiction genres in our literature.15

In his Viaje Maravilloso del Señor Nic-Nac (1875) the figure

of the immigrant comes to us accompanied by a “counterfigure”:

that of the Creole or “national type” who is shown to be

“absorbed, devoured by the whirlwind of an inexplicable

cosmopolitanism”. Although the decrease in the image of the

national in the face of the weight of immigration will be a very

frequent topic from 1880 onwards, it already constituted the

framework of the conversation between Seele and Nic-Nac in the second

part of the novel.

In any case, the quintessential character

who will characterize the image of the national during these years

will be Juan Moreira (1879-1880)

by Eduardo Gutiérrez, the gaucho who carries with him the anathema

of being the son of the country, the one who has a hard time getting

a job because in the ranch they prefer that of a foreigner; who kills

an immigrant even if it is not worth it, even if he has to flee the

country. Because there is no possible pact with his counterpart, this

one was a businessman and Moreira says he does not have “the skin

for business.”16

The

conflict between creoles and immigrants will find a literary solution

in the already mentioned La gringa (1904), by Florencio Sánchez,

where as we said the conflict is overcome through the fusion of the

races that have needed each other, just as Carolina also said to

Laucha in Payró's novel: “What I needed was a ‘coven’17

like you.”

In 1909, Ricardo Rojas published La

Restauración Nacionalista, a text that articulated the most

heated polemic, appearing months before the first Centenary

celebration.18

In this book, Rojas warned about the dangers that the family, the

language, and the entire country were facing due to the prevailing

cosmopolitanism, proclaiming: “Let us not continue tempting death

with our cosmopolitanism without history and our school without a

homeland.”19

On November 17 of that same year, at the funeral of Ramón Falcón,

chief of police murdered by anarchists, a series of distinguished

citizens spoke out against immigrants, concluding that “the

cosmopolitanism of our laws has brought us to the brink of social

disorganization.”20

The nationalists also maintained that immigration destroyed the

Argentine character and patriotism, railing against foreign music and

also against tango, the last one seen as a “repugnant, hybrid,

unfortunate music” and “a lamentable symbol of our

denationalization.” Gálvez, Rojas and Lugones were some of the

main standard-bearers of the gaucho, Creole, traditional

counterfigure to confront cosmopolitanism and immigration. And José

Ingenieros would add to this debate in Sociología Argentina

(1913) with an irony: the children of foreigners almost always become

patriots. The figure becomes a counterfigure. The stage for the

Centennial celebration was dressed for the occasion with countrymen,

taming and branding gaucho ceremonies, but the Prussian uniforms and

the public made up of immigrant families insinuated that the

autochthonous airs were only a decoration offered to the foreign

delegations in the midst of a markedly European ethnography and

architecture.

An interesting work in this regard written in

the year of the Centennial is Los gauchos judíos, by Alberto

Gerchunoff, testimony of a process by which a foreigner chooses to

become an Argentine citizen. The author is thus the spokesman for an

experience that constitutes one of the characteristics of the

construction of the Argentine nation since the 1980s: the mixture of

races and cultures in a country that needed to populate the space in

order to govern, as Juan Bautista Alberdi had seen years

before.

The national question had brought the figure of the

gaucho to the table of discussion on identity, now loaded with

positive values and presented as a response to immigration,

but, on the other hand, the foreigner appeared with equal force.

On

the one hand, the conflict makes nationalists like Lugones, Rojas,

Manuel Gálvez and Joaquín V. González think, and on the other,

some sons of immigrants who, in the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters

and in magazines like Nosotros, welcome the incorporation of

the foreign component into the formation of the national being. Among

these are the already mentioned Gerchunoff, Payró, the Italian

Roberto Giusti, Rafael Arieta and Arturo Marasso, defenders of

cosmopolitanism, the coexistence of dialects and socialism. They do

not seek the past or the “voluntarist” vindication of the

indigenous or the gaucho but the future through immigration.21

On

the nationalist side, the project to invent the identity of the

country initiated by J. V. González with La tradición nacional

(1891) is completed with two other books: El juicio del siglo

(1910) and Mis montañas (1923). The writer warns in them

about the need to reflect seriously on the laws that should guide the

progress of Argentine society, taking into account the wave of

immigration, the imminence of mass movements, the relations between

new classes and the economic opening to the world.

Until

then, many Argentines ignored gaucho literature. The gaucho was

disdained as an obstacle to civilization. But with the traditionalist

and nationalist resurgence, the gauchos

become prettier and the gringos become ugly, they become

grotesque due to their often failed greed, generating a new conflict

already mentioned in this game of figures and counterfigures:

immigrant parents and Creole children.

In short, when

immigration appears, nationalist resurgences appear. This game is at

the center of the modernization process that is constituted, first,

by leaving the gauchos aside, and then by excluding the immigrants

themselves in the (only symbolic) recovery of the

former.

Cosmopolitan cultural refinement will continue to be an

indelible mark of identity after 1920, but now linked to a

revaluation of the Creole heritage, unthinkable in the last decades

of the 19th century. To a certain extent, this fusion was also

condensed in literature by Ricardo Guiraldes' Don Segundo Sombra

(1926), whose character - unlike what happened in Martín Fierro

- will coexist peacefully with it without worrying too much about its

existence.

Mixtures marked these decades: a time of

experimentation in laboratories like the one we saw in El hombre

artificial and test tubes that will mix many things: blood,

language, nations and finally classes to create what Ramos Mejía

will call the “guarango” in Las multitudes argentinas

(1899).22

In

the already mentioned La gringa, by Florencio Sánchez,

Nicola's children have become creoles, the immigrants give in to the

near fatality of exogamy in a foreign land. The optimistic ending -

"From there the strong race of the future will emerge" -

humanizes both parties who understand each other in the fusion. And

in the also already mentioned El casamiento de Laucha, all the

languages (Neapolitan, gaucho, cultured, the language of the

province) are spoken in a story that is in turn a mixture

derived from two genres: the gauchesca and the picaresque.

Laucha, a middle-class Creole, a rascal, knows how to read and write

and makes an alliance with the two immigrants, Carolina and the

priest. He forges with both of them. He pretends to reach the capital

and uses any means. When he speaks with the Spanish grocer, their

lives mix, as music will also mix in those years to give rise to

tango.

The passion for enrichment linked to the position of a

double European-American identity is in the history of our Latin

American literature from the conquest (with Garcilaso) to the Italian

immigrant who not only splits his nationality but also his

profession: the school teacher also keeps the accounts of various

business houses; the shoemaker sells lottery tickets; the typist has

a tailor's shop; the grocer sells everything; arts and commerce are

combined in the immigrants who can be several things at the same

time, always trusting in that utopian dimension of America.

Double

identities then populate the period; the character of Marco Severy

being a criminal in Italy and an honest man in Argentina, like so

many “converts” in the history of travel from Europe to America,

or as seen in the autobiographical novel Las dos patrias

(1906), by Godofredo Daireaux. In all of them we find an immigrant’s

desire to excel, traceable from the chronicles and narratives of the

Conquest to José Ingenieros, a successful immigrant but also a

pretender who changes his name to rise and constitutes the new great

Argentine that everyone dreamed of being. They all seem to want to

succeed, to become famous or rich, which resulted in the

multiplication of identities, even in their jobs. That is why it is

so difficult to say what we Argentines are. Perhaps that is it: a

desire.

Daniel Scarfò

1 See Losada, Leandro. La alta sociedad en la Buenos Aires de la Belle Époque. Buenos

Aires, Siglo XXI, 2008.

2See José M. Ramos Mejía, Rosas y su tiempo. Buenos Aires: Emecé, 2001 and Juan Agustín García, La ciudad indiana. Buenos Aires: Hyspamérica, 1986.

3Daireaux, “Aristocracia de antaño”, quoted by Losada, Leandro (2008). All translations in this document are mine.

4 Arlt, Roberto. Los siete locos. Los lanzallamas. San José: Universidad de Costa Rica, 2000, p. 440

5See Quesada, Ernesto. El problema del idioma nacional, Buenos Aires: Revista Nacional Casa Editora, 1900.

6 See Viñas David. Grotesco, inmigración y fracaso: Armando Discépolo. Buenos Aires: Corregidor, 1973.

7 Cambaceres, Eugenio. En la sangre. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Colihue, 2008, p. 108. This definition reveals the pejorative bias that surrounded gaucho origins in the 1880s. Similar notes can be found in the Divertidas Aventuras del Nieto de Juan Moreira by R. Payró, published in 1910.

8 Cambaceres, op. Cit. p. 154

9 See Elías, Norbert, El proceso de la civilización. México: FCE, 1988 and Sennett, Richard, El declive del hombre público. Barcelona: Anagrama, 2011.

10 Vicente Quesada's pseudonym.

11In South America (1894), ¿Adónde vamos? (1904) and La creación del mundo moral (1912)

12See Losada, Op. Cit.

13From here, the grotesque genre would emerge -after a previous step through the Creole sainete- with El organito (1925), combining with the picaresque in Armando Discépolo. David Viñas maintains in this regard that "in the grotesque-picaresque of Armando Discépolo the characters of the liberal city are summarized, and if up to here they were repeating Cambaceres, perhaps Payró or Fray Mocho, or contemporary Arlt, with this 'madhouse' where cornering and gloom as a whole predominate the moral scenery is what materializes the deterioration. From the optimism prior to 1919 we had moved on to cautious pessimism, to skepticism; but now we border on cynicism: evil is neither conjured nor justified, it is assumed and also 'internalized'" (Viñas: 1973). Although it retains the clichés of the farce - thwarted love, pretense, jealousy, tensions between foreigners and those born in the country - in the Creole grotesque novelties appear such as the scrutiny of human relationships, the pessimism of men and hypocrisy.

14 Viñas argues that there were then seven alternatives for the “unworthy” immigrant: invent, steal, prostitute (prostitutes, maintained ones, pimps, informers or servants), go mad (“or immerse oneself in the whole range of imbecility”), commit suicide, flee (“specifically with the spiritual variant of entering a convent”) or get even with the old immigrant or the parents (Viñas forgets the variant of the army). But the figure of the immigrant can only be read as a figure of failure if it is read with candor. It is not about reversing the place of evil. Although the “evil” were not the immigrants, neither was it outside the constitution of their subjectivities in the process of modernization.

15 Holmberg was a precursor in Argentina of what C. P. Snow would call the “third culture” in the mid-twentieth century, which affirmed the advantage of being a scientist and a man of letters, since he believed that they were two ways of looking at the world that were not opposed but complementary. He was also one of the founders of the Revista Literaria (1879), an organ of the Círculo Científico Literario, a publication that brought together scientists and writers.

16 “Cuero para negocio”. Gutierrez, Eduardo. Juan Moreira. Barcelona: Red Ediciones, 2012, p. 207.

17“Joven”, young person, pronounced in “cocoliche”, a mix of Italian and Spanish spoken by the Italian inmigrants.

18 In 1810 the May Revolution established the first local government on May 25.

19Rojas, Ricardo. La restauración nacionalista. Bs. As.: Ministerio de Justicia e Instrucción Pública, 1909, p. 347-8.

20La Nación, Bs. As., 17-11-09

21 In 1911 Giusti published Nuestros poetas jóvenes, Revista crítica del actual movimiento poético argentino where he mainly railed against Rojas, especially regarding his La Restauración Nacionalista, maintaining that it is foreigners who will make history.

22 Regarding the mixture of languages, an article published in Caras y Caretas in 1900 entitled “Modificaciones al idioma” maintained that the confusion of the Tower of Babel is “nothing compared to what is happening in our language”. And again Cané in “La cuestión del idioma” (La Nación, 10-5-1900), affirmed that no great literature could emerge from the devastation of language.

-

Conociendo a Xul a través de Borges Podemos conocer a un hombre a partir de sus libros. Xul Solar vivió los últimos años de su vi...

-

"Nosotros (la indivisa divinidad que opera en nosotros) hemos soñado el mundo. Lo hemos soñado resistente, misterioso, visible, ubicuo ...

-

Del Marco a Amarcord: tres vueltas de llave y un crítico o As time goes by Ya escribí algo sobre este cuento. La lectora lo sabe. Pero ahora...